Introduction

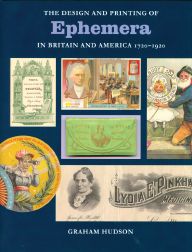

THIS BOOK CONSIDERS the changing appearance of British and American printed ephemera over a period of two hundred years and discusses the part played by design in the thinking of those who created it.

Produced to meet the needs of the passing day, in content and form ephemera are wholly part of the culture within which they are created. This has nowhere been better expressed than in Arnold Bennett's Clayhanger, where the author evokes a picture of old Clayhanger's printing shop, its dusty ephemera of old jobs hanging from the rafters and proof sheets of current work scattered here and there below:

These printed things showed to what extent Darius Clayhanger's establishment was a channel through which the life of the town had somehow to pass. Auctions, meetings, concerts, sermons ... bill-heads, hand-bills, addresses, visiting-cards, society rules, bargain-sales, lost and found notices: traces of all these matters, and more, were to be found in that office: it was impregnated with the human interest; it was dusty with the human interest; its hot smell seemed to you to come off life itself.'

Though separated from Bennett's Five Towns by close on six thousand miles of land and ocean, the Ohio print shop that novelist T. B. Howells remembered from childhood turned out much the same range of work; but it was the craftsmen who did the printing that formed Howells's earliest recollections: 'the compositors rhythmically swaying before their cases of type; the pressman flinging himself back on the bar that made the impression ... the apprentice rolling the forms, and the foreman bending over the imposing stone'.

These were letterpress printers, but though the ephemera that one studies and collects today are as likely to have been printed from an engraved plate or a lithographic stone as from type and blocks, the ambience of the workshop will have been much the same.

The Encyclopedia of Ephemera contains well over five hundred separate articles, covering subjects as diverse as: ballad sheets, 'at home' cards, billheads, dance programmes, funeralia, inn tallies, posters, sheet-music covers - everything from 'ABC primer' to 'Zoetrope strip/disc'.

To consider the design of each of these individually is scarcely feasible, and would indeed be repetitive, for the factors that have affected the design of each of them are those that have affected all. It is therefore these factors, and the part they have played in the changing appearance of printed ephemera, that are the subject of this book. The factors are three: function, process and period.

Function is self-explanatory, for it concerns the purpose for which an item of ephemera was produced. Illustrated writing paper intended for private correspondence was naturally presented differently from commercial stationery; and a circular was graphically different from a poster, the one small for leisurely perusal, the other larger, and more boldly displayed to attract attention in the busy street.

Process relates to the means by which ephemera were printed. In the period under discussion these would chiefly be letterpress, engraving or lithography, and their related media and methods, e.g. wood-engraving, engine-turning, printing in gold, lace-paper decoration, etc. Each of these had its individual qualities and thus, either clearly or with subtlety, each had its effect on the look of what was printed. The letterpress printer could set several hundred words for a leaflet or programme in a fraction the time it would have taken an engraver to etch them in copper, and this would be equally so with ephemera utilising more limited copy, such as a trade card or a ball invitation. Yet letterpress also imparted a characteristic horizontal and vertical stress on printed matter that was not easily disguised, while the engraver suffered no such limitation, leaving him free to create designs as complex and elegant as he could wish or his customer would pay for.

Period concerns the historical period in which an item of ephemera played its brief part in the historical record. Here the effects on design are expressions of both commerce and culture. Improving communications in the eighteenth century brought the large typefaces needed for the printing of easily seen mail- and stagecoach bills, while tradesmen's cards were tricked out with the Rococo detail that elsewhere found expression in contemporary domestic furniture; and on ephemera also, the purveyors of hardware, patent medicines and other goods once household names presented their wares, and vaudeville and music-hall stars now long forgotten enjoyed their floreat days.

The design histories of ephemeral printing in Britain and America are inextricably woven. Colonial printers and engravers imported British type and equipment, took instruction from the same manuals, drew inspiration from the same exemplars. In 1798 the establishment of the first successful American type-foundry gave American printers a source of type nearer home, but those types were cast with strikes from British founders' punches; and though American punch cutters were to be at work early in the following century, the forms of their bold new display letters would be closely modelled on those of Britain.

It was in the years of stability and enterprise following the Civil War that American graphic design established its own identity. In Britain printing in colours was achieved by a variety of means but in America colour printing meant essentially chromolithography, and the focused development of this process in the latter part of the nineteenth century resulted in an efflorescence of colour-rich trade cards, cigar-box labels, rewards of merit, calendars and other ephemera that was essentially American. In Britain from the 1860s, typeface design stagnated, but from America a wealth of inventive new types now crossed the Atlantic en route to printing offices in London, Edinburgh, Dublin and elsewhere. Yet ideas travelled in both directions, for the development of expertise in designing with these new typefaces (and other innovations of the period) depended on jobbing printers learning from each other, and the scheme of specimen exchange that achieved this was set up in and administered from London.

The art of the printer relates as much to artifice - the making of things - as it does to Art, but while most printers of ephemera would not have claimed to be fine artists (though some in the later nineteenth century would do so) it is self-evident that many did exercise aesthetic considerations when laying out their work. The difficulty is - whether concerning visual qualities or adherence to particular conventions - printers rarely put pen to paper regarding why they did what they did: their work was too much an everyday activity to warrant record. A case in point is the long, narrow Victorian playbill, discussed on pages 00-0: the reasons for the development of this format must have been common knowledge in the trade, but in the absence of written record we can now only surmise. One has to glean what one can from the early manuals and - fortunately in rather more detail - the occasional articles in the trade journals. As to why a particular printer chose this type or letter-form rather than that or one arrangement rather than another, we cannot know; though we may realistically surmise.

It was in the 1720s that the young Benjamin Franklin worked for a period as a printer in London, before returning home and starting his own business in Philadelphia. All then was grist to the printer's mill - books, newspapers and general jobbing. A century or so later those three aspects of the one trade would become separate fields, with jobbing printers large and small undertaking the endless miscellany of trade cards, playbills, music covers, posters and other classes of ephemera now so avidly studied and collected.