INTRODUCTION

Kevin Johnson

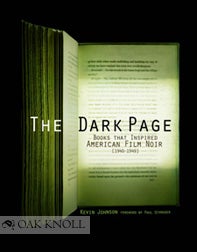

Welcome to The Dark Page, a book about books, a book about American film noir, and a book about the novelists, screenwriters, and directors that make up the fascinating and rarely discussed relationship between the two. Every book you see in the pages that follow has been documented for the same reason-it was the basis for a film in the American film noir cycle during the 1940s. Before going into the criteria for book selection, I'd like to first discuss a few basic ground rules about the films themselves.

A Definition of Film Noir

The first step in understanding the American film noir cycle is to obtain a better grasp of just what "film noir" is and what it is not. I find that film enthusiasts sometimes have a shaky understanding of the term, due mostly to the casual way it is defined in popular culture. Film noir has in fact been the subject of much scholarship since the 1940s, beginning in France and moving later to the United States, and has a well-established critical history that is unknown to the average filmgoer. The collision of this scholarship with the huge popularity of films noir has resulted in some major misconceptions.

The first and most common misconception is that film noir is a genre, when it is in fact a style. The noir thread runs through virtually every genre, including Westerns, melodramas, science fiction, crime, and horror. The 1950 sci-fi classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a film noir, as is the 1948 Western, Blood on the Moon.

The second most common misconception is that a film noir always involves detectives or a crime. While these elements are commonly found in films noir, they do not define the style, nor does the style require their inclusion. Noir protagonists run the gamut from housewives to bankers to journalists, and while a criminous element is typically somewhere to be found, it is often subtle, tangential to the story, or even altogether absent.

The third most common misconception is that film noir is meant to be a broad term, covering everything from a film like The Maltese Falcon to Roman Polanski's Chinatown to the Coen Brothers' The Man Who Wasn't There. The film noir cycle, by critical consensus, did not begin until 1940, and depending on who you ask, ended somewhere between 1959 and 1965. Key crime films before 1940, such as Little Caesar or Beast of the City are considered noir antecedents, with the distinction being that all the elements of noir had not yet come together. Films after 1965 are considered post-noir or neo-noir, and that dividing line is based on the point at which noir films became "self-aware." In other words, once filmmakers were consciously making films in the noir style, the original cycle had effectively come to an end.

The noir style is defined as a combination of several elements that came together in American film beginning in 1940. Speaking generally, three of those elements are (1) the arrival of German directors and cinematographers in Hollywood during both World Wars, who brought with them the expressionistic style of German films of the 1920s and 1930s, (2) a cultural malaise in America, resulting from both World Wars, that brought about a more cynical outlook and a strong response to darker themes, motivations, and story lines in films, (3) Hollywood's adoption of the "hard-boiled" school of storytelling, which had existed in print since the early 1920s, but did not reach full realization on the screen until 1940. There are other factors as well, such as the rigidly structured Hollywood studio system, which accommodated the aforementioned elements and caused the noir style to flourish once it became popular with audiences.

Recommended Reading on Film Noir

The Dark Page is built on a foundation of existing scholarship on film noir, but is meant only to be an in-depth study of the book sources themselves. The two best pieces I can recommend with regard to a comprehensive definition of film noir are by Paul Schrader and David Spicer. Schrader's seminal 1971 essay, "Notes on Film Noir," which has remained completely relevant and undated over the past thirty-five years, can be found in Film Noir Reader, edited by Alain Silver and James Ursini and published by Limelight Editions in 1996. David Spicer's book simply titled, Film Noir, published by Longmans in 2002, is the most straightforward and thorough primer on the subject I have ever read, with detailed discussions of everything from the expressionist origins of the noir style to the role of the Hollywood system in its development.

Film Sources

In determining a source list for The Dark Page, I used as my template the work of three film writers whose published books on the films in the noir canon I found to be the most deeply rooted in careful research and thought. My primary reference is Dark City: The Film Noir by Spencer Selby (McFarland,1984). Selby's book is an extraordinarily comprehensive study of American film noir, published well before most of the many American books and articles on the subject that followed it, with a scope that has never been improved upon. Among Dark City's few significant antecedents in English are Raymond Durgnat's "The Family Tree of Film Noir" (Cinema, August 1970) and Paul Schrader's essay noted earlier. What makes Selby's book singular is that it attempts to identify all the American films in the noir canon, with an eye for detail and an understanding of the scholarship that preceded it. Selby is at work on his magnum opus, an expanded, comprehensive guide to the American, British and Western European films in the cycle.

My two secondary references are two books that I feel are both complementary to Selby's work, but in different ways. The first is Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference, edited by Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward (Overlook Press, 1993). Now in its third edition, the Silver and Ward guide is one of the most articulate studies of American film noir, and while it is not as exhaustive or inclusive as Selby's Dark City, it stands on its own as an important and detailed study, particularly in the case of films from the major studios. Also, there is no better reference for detailed plot deconstructions of the major films in the cycle.

My other secondary reference is Death on the Cheap: The B-Movies of Film Noir by Arthur Lyons (Da Capo Press, 2000). Lyons' book focuses almost exclusively on the important films noir that were released outside of the major studios, many of which are today considered classics of the genre. These films were among the first to successfully subvert the Hays Code and have remained the most difficult to locate in any kind of viewable format. Like Selby, Lyons is at work on a revised edition of his book.

Book Sources

The range of literature that constitutes the basis for American film noir is surprisingly broad. While a number of the sources are crime novels as one would expect, many fall well outside that category. Some are romances, some are examples of great western literature, and a few are even nonfiction. The range of authors runs the gamut, starting from the giants of high literature from the past two centuries (Henry James, Aldous Huxley, Ernest Hemingway, Ayn Rand, W. Somerset Maugham, Graham Greene, Robert Louis Stevenson) to its classic crime authors (Wilkie Collins, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett), to its "cult" authors who never quite received their due (Geoffrey Homes, David Goodis, B. Traven), and finally to the weird and intriguing heap at the bottom, a healthy dose of authors who languish in obscurity, whether deservedly or undeservedly (Robert Du Soe, Martin Goldsmith, Ernst Lothar, John Taintor Foote, and many others).

While it is a strongly held belief among some bibliophiles that a book has an inherently greater legacy than a film, there are more than a few arguments to the contrary. There are numerous cases where a legendary film is based on a book that is completely forgotten or long out of print; and conversely, in the defense of said bibliophiles, cases where a legendary book has been made into a mediocre film. Since opinions on this subject vary widely, I've made an attempt to give every book source and related film in the American noir cycle equal consideration, without attempting to assign rank or relative importance.

A Note about Attribution

The content of the book and film "discussions" found in each entry, sometimes paraphrased and sometimes quoted directly, is drawn almost entirely from other sources. The discussions are meant to be light and factual, and I've made no attempt to shed new critical light on any book or film. Rather, my goal was to include interesting information about authors, screenwriters, and directors that would make for a good accompaniment to the core content of this guide, that being the books themselves.

Credit for the sources used is attributed either at the beginning of a quote, or at the end of a given section. In cases where one source provided content for the entire entry (i.e., both the book section and the film section), the source is credited only once, at the end of the entry.

How to use this book

The entries in this volume are presented in alphabetical order by book author, and within a given author, by the order in which the books were adapted to film. This sometimes results in a sequence that will be unfamiliar to book collectors. For example, Raymond Chandler's second novel, Farewell, My Lovely was made into a film before his first novel, The Big Sleep; hence, Farewell, My Lovely is shown first.

Each entry begins with the book title, author, and publisher of the first edition, followed by a discussion of the book and/or its author. Next are the book points that identify the first edition, which include any information that cannot be clearly seen in the photo to the right of the description. The second part of each entry is devoted to the film made from the book or a short story from the book, beginning with the title and film director, followed by detailed information regarding the screenwriter(s), film studio, cinematographer(s), actors, and composer(s) involved. A discussion of the film follows, ending with a notation of the scholarly reference used to qualify the film for inclusion in the 1940s American film noir cycle.

What is a Contributor?

After each book and film entry, you will see a brief paragraph with information about each "contributor," and where that person's "contribution" fits into the 1940s American film noir cycle. In the context of this book, a "contributor" is defined as an author, a film director, or a screenwriter that had some intersection with a literary source. In a few select cases, film producers are noted as well. For example, if a sentence reads, "John Huston's second of five contributions," it means that the entry you are reading about is the second film in which John Huston was involved, either as a screenwriter or a director, during the 1940s. Since some of the contributors' entries do not involve literary sources (e.g., John Huston's contribution to Three Strangers as a screenwriter in 1946), a Selected Filmography of Key Contributors is provided at the end of the book, which shows every contribution by a given individual during the 1940s, including original screenplays. A discussion of this section follows.

Selected Filmography of Key Contributors

Early on in the research process, I found a significant intersection of authors, screenwriters, and directors in the world of 1940s American film noir. Prolific screenwriters like Richard Brooks and Jay Dratler wrote obscure novels, and famous novelists like Ayn Rand, William Faulkner and Raymond Chandler worked as screenwriters in near-anonymity. Many films noir were based on plays, many of which were hits on Broadway, and others that barely made it past opening night. In the case of Ben Hecht, one man functioned as author of the book source, screenwriter, and director. The Selected Filmography shows the order of contributions by each writer, director and screenwriter, and the list includes films that were based on books as well as those based on original stories, unpublished plays, or screenplays.

If a contributor to the 1940s American film noir cycle has no intersection with a literary source, that contributor is not discussed in The Dark Page. Examples of directors in this category during the 1940s would include Douglas Sirk and Elia Kazan. This certainly does not mean that the contribution or the film was insignificant, it simply means that the contributor's work has no connection in the 1940s to a literary adaptation. For a more complete list of films noir, I recommend the aforementioned guides by Selby, Silver and Ward, and Lyons.

Guidelines for Selection of First Editions

The book types considered in this volume are limited to sources for films noir made between 1940 and 1949, and include the following:

Novels and plays, published either in hardcover or as paperback originals

Short stories published in collections

Nonfiction books used as a film source

The following book types are not considered:

Novelizations of films (with a few important exceptions)

Photoplay editions

Actors' softcover play editions

Novels or collections of stories that were published long after the release of a film

Magazine, digest or pulp appearances

In the cases where a film has two book sources (or the book has two significant binding or jacket variants), the primary source is pictured in the Main Bibliography, and the secondary source is discussed in Appendix A: Secondary Book Sources.

In the cases where a book has content that is the basis for more than one film, the first produced film adaptation is discussed in the Main Bibliography, and the later film adaptations are discussed in Appendix B: Secondary Films.

In the cases where the photo for a rare book source has been reconstructed based on available information, the entry appears in Appendix C: Reconstructed Book Sources.

Types of editions

In cases where the trade first edition of a book was preceded by or issued simultaneously with a signed limited edition or presentation edition, preference is given to the trade edition.

American, British and foreign first editions

In the case of first editions in translation (works originally written in a language other than English), the first edition in English is given preference.

Within the scope of English-language editions, a "follow the flag" position is taken in the matter of correct first editions. This means that the country most strongly associated with the author's nationality (typically either the United States or the United Kingdom, but occasionally other countries) is the preferred country of first edition publication.

Book Points

First edition points are provided for each book just below the description of each book source. For those unfamiliar with the terminology used in the description of a book, I recommend John Carter's ABC for Book Collectors, published by the Oak Knoll Press. For a more general overview of first editions and book collecting, I recommend Book Collecting 2000 by Patricia and Allen Ahearn, published by Putnam.

Condition, scarcity and book values

A conscious effort has been made to avoid discussion of condition, scarcity and value of books in this volume, as this information is constantly changing.

Regarding Photographic Reproductions of Books

The books represented in The Dark Page came from many sources, including major institutions, personal libraries, and the photographic archives of rare booksellers. Our goal was to reproduce with complete accuracy the first edition of the book described in each entry, with extreme attention to detail regarding color, size, texture, and most of all, the correct representation of the book details. Most of the books you see in the pages that follow are actual photographs of a given book. In the case of a few extremely rare books, however, the book and jacket have been carefully reconstructed from parts that exist in different collections, often located in different parts of the world. In only one instance did we have to make a "guess" at the accuracy of a given representation, and that single volume is in Appendix C (Reconstructed Books). It is important to understand that the representation we present is that of a "perfect" copy. That representation may (or may not) have involved digital manipulation, combination of parts, and other techniques.

Future volumes

Two future volumes in this series are envisioned. The second volume will cover the book sources for American films noir released between 1950 and1965, and the third volume will cover British and European films noir.

A Final Word

The last days of tracking down photographs of the first editions in The Dark Page were truly dramatic. After years of effort, two months prior to our deadline, it still appeared that there would be at least a dozen titles we simply weren't going to find. Then, at the eleventh hour, we had one magical break after another, and by the end of July 2007, literally forty-eight hours before submitting our manuscript, the last photo (one of the rarest Haycraft Queen cornerstones, Israel Zangwill's The Big Bow Mystery) was inserted. To say the hunt was a thrill would be an understatement at best.