Postscript: Is typography necessary? PUBLISHERS and even printers have been known to smile indulgently when watching a typographer pondering the proof of a title-page long and earnestly and at last marking a point of space in between two capital letters. What does it matter, they ask, and was it not perfectly legible before?

Legibility is not enough to aim at when one is printing books. True, G. K. Chesterton said that if a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly. And a poorly printed copy of a favourite book is better than no copy at all. Probably everybody will agree that a well-produced book is better than a moderately-produced book. The difference between the two is small. Is it worth the extra trouble? will one point (one seventysecond of an inch) be noticed? Does typography matter?

Assuming that anything matters. then certainly it matters how things are made and what they look like, and typography is responsible for how printed words are made and what they look like. Many books today are printed in good types, on quite good paper. and yet the result is only moderately pleasing. An enormous amount of skill (five hundred years of it. at least) has gone into the design and manufacturing of the types; the brains of engineers and scientists of many generations have gone into the making of the paper and the ink and the printing machinery; and highly skilled craftsmen have done the actual printing. It has lacked one ingredient, the brains of a typographer. and so is by that amount less good than it should have been.

The fact that good types are available at all today is due to typographers' efforts in the past; that work is now done, and a publisher can be sure that every book printer today is stocked with several excellent founts of type. Of what does typography consist when applied to the actual production of a book?

The first and all-important principle is that the type matter should be so arranged that the author's message is transferred to the reader's brain as quickly and smoothly as possible; the mechanism by which this is achieved should not be noticeable. If one is judging a new type face. one looks at a page of it. and if any letter springs to the eye. even as being particularly beautiful, that letter is wrong.

A great many modern books offend by trying hard to be well designed or 'modern', and there certainly are cases where the contents matter so little that a piece of clever design relieves what would otherwise be boredom; but in all real books, the book is the author, and not the printed page: it is just as annoying when the printer or typographer obtrudes his personality into the author-reader relationship as when some outsider rings a bell for tea or switches on the telly.

But if some books are spoiled by too much typography, more books are spoiled by having too little. One of the first concerns of a typographer in planning a book is to decide on the size of type that will be right for the size of page, and for the length of line, and to determine the amount of leading required. Normally there should be not less than ten words per line on a book reading page, and not more than fifteen: too short a line means turning back too often, and too long a line means losing the right line when you turn back. The amount ofleading, or white between the lines, depends partly on the length of the ascenders and descenders of the fount. Most type is easier to read if it is slightly leaded. It is also a rule of good composition that setting should be close, and as even as pos

sible; the space between words should be about the width of the letter 'j',

and never much more. The longer the gap between words, the harder the work for the eye, and the greater the risk of a word in the line below being nearer than the next word, in which case the eye will jump to it instead. Also, when spacing between words is too wide, ugly rivers of white appear, and the even grey texture of a well-set page of type is lost.

Margins are also important. They are the frame surrounding a page of type and separating it from the scenery in the background. In the old days, when people read books seriously, they were used for making notes, and they were always as generous as possible because every time a book is re-bound, something more is sliced off all sides. Nowadays the convenience of having books we can slip into the pocket and the exigencies of wartime have made us less sensitive to margins and we find we can, when necessary, do with very narrow ones. Sometimes, modern books are printed with normal margins reversed, i.e. with the outside margin narrower than the inside margin. If such books will never need to be re-bound, there seems no technical argument for this. It merely looks awful.

There are a thousand other details in which good typography can improve a book, and one seventy-second of an inch may in fact make a noticeable difference. That all made things should be made as beautiful as possible is one of the details in which civilisation consists. It is no more important that books should be well-made, than that anything else should be well-made; unless, indeed, you happen to regard books as friends. We do not want our friends all to be well-dressed, but we do, I think, want them all to be comfortably and appropriately dressed. Therein lies the pleasure and the skill of book typography.

ANYWAY, what is a typographer?

I am writing this in the UK, where 'typographer' does not mean, as it does in the USA, the man, woman or firm who sets the type. I mean the designer.

But today, when there are so many different terms covering so many different activities - layout staff, graphic artists, 'graphikers', visualisers, etc., - let us use the word 'typographer' in its traditional sense of the person who lays out or arranges type in order to be read.

As opposed, for example, to the graphic designers who make 'images', who use not words but symbols, shapes, photographs and other visual ideas. That is something completely different. The tWo skills are not often found in the same person.

The typographer, then, in the original sense of the word, uses type to communicate an author's message. For many years after the invention of moveable type way back in the 1400s, the typographer was always the printer. In a famous book published in London in 1683-4, called Mechanick Exercises or the Whole Art of Printing, the author Joseph Moxon wrote 'by a typographer, I mean such a one, who by his own Judgement, from solid reasoning within himself, can either perform, or direct others to perform from beginning to the end, all the Handy-works and Physical Operations relating to Typographie'. That still does not define the actual job. But Moxon was writing a manual, and went on to describe those 'Handy-works and Physical Operations' in detail.

Putting words together, letter by letter in the composing-stick, was the job of the compositor. 'A good Compositer, [sic]', wrote Moxon, 'is ambitious as well to make the meaning of his Author intelligent to the Reader, as to make his work show graceful to the eye, and pleasant in

Reading'. That says it all. Designing printed matter so that the words 'show graceful to the Eye, and pleasant in Reading' continued to be the work of compositors for centuries. They sometimes worked on their own, but more often under the direction of the Master Printer.

By the end of the nineteenth century, Monotype and Linotype hot-metal composition systems had both been invented (in the United States). The old days of hand-setting, hand presses and hand-made paper were ended. The Master Printer now had to master a lot of new techniques, including machines run by steam and electricity, not to mention the host of new typefaces made possible by the Benton punch-cutting machine. His hands were full. No wonder that he had to look around for someone else to attend to the finicky details of typographic design.

Since many of these new developments came from America, it is not surprising that the first freelance typographer, Bruce Rogers, and the first freelance type designer, Fred Goudy, were both Americans.

But typography did not become a profession, in which you could be qualified, and be awarded a degree, as in medicine, accountancy and architecture, until much later. In Britain certainly it came only after 1945. But the job remained the same: to make words 'graceful to the Eye, and pleasant in Reading'.

It is a more complicated job than at first may appear. There are many different kinds of book, let alone the modern visual aids, and there are many different kinds of text: some, like dictionaries, that you usually only want to read a few words at a time; some that have to be read very carefully and perhaps re-read several times; others that have to be skimmed through very quickly in order to find a needed reference or fact: and the ideal type and typographical treatment for each may be quite different.

Aren't the author's words sacred?

It depends.

When a typographer is given a work of literature—poems, prose, or whatever—then of course the words, or punctuation? or use of capitals?—may not be changed without the author's permission. Authors, like everyone else, make mistakes—some are very grateful when they are corrected, others less so! But mistakes (e.g. quotations from the Bible, or other words of printed literature) have to be corrected.

But not all typography is book typography, in which the words are usually sacred. Magazine, brochure or newspaper texts, especially headings, often can, and even must be changed. In a magazine, the title of an article usually has one main purpose: to tell the reader what the article is about, to give him or her the choice whether it's a 'must' or can be skipped - or in some 'popular' journalism and in advertising, to try to make the reader want to read it. Designers must have the freedom to suggest better wording for a title, perhaps to fit a space or an illustration that the original writer did not know about.

All experienced typographers know that in many kinds of work words that come to them are not right. In a letterheading for example, it is surprising how often the client supplies the wrong street number or postcode, or leaves out some important wording completely.

I once had to design a poster for the notice-boards of a university, telling graduates and undergraduates how to register for their courses at the beginning of the academic year. The university could not understand why the existing poster was being ignored.

I sat down to read the 'copy' I was given. It took me all of three hours to puzzle out what the man who wrote that copy was trying to say. He could not write plain English - a gift, like that of 'common sense' which is not so common as you may think. Having, with many doubts, arrived at what I thought was meant, I re-wrote the copy and returned it to the university saying (apologetically) 'Is this what you mean?' It came back saying 'Thank you, yes'. The 'typography' was then easy. But with a text that did not make sense, it was impossible.

The words have to be right.

(Some of the above was originally printed in The Folio, Vol. 1, No. 5, May-June 1948.)

|

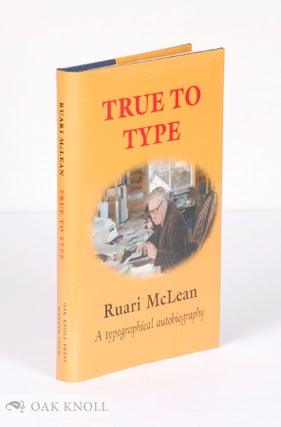

| The author in Carsaig library, 1990. (Photo by Colin Banks.) |